Hap-mu

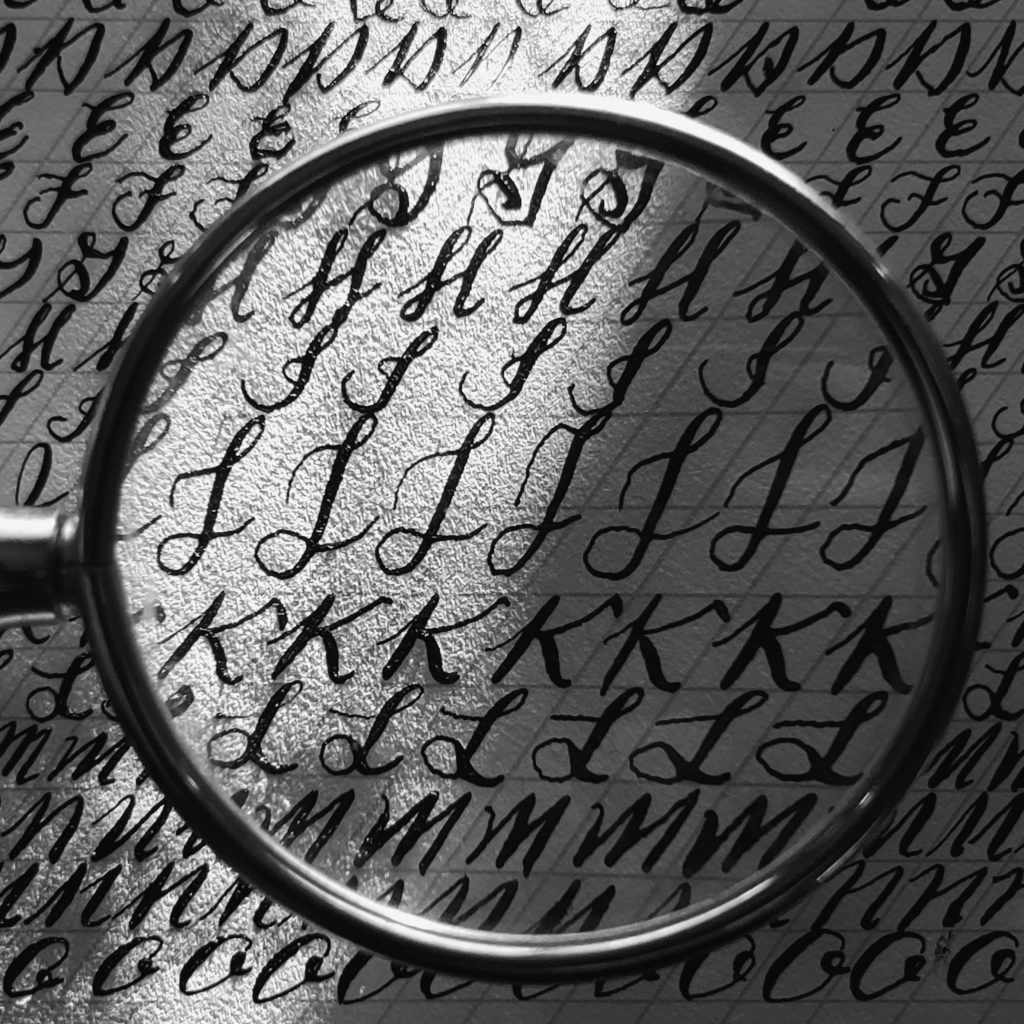

“No, no,” Meryre said. “Make longer strokes here.” He tapped the clay shard on my knee with his brush. “Your Ba’s tail is too short.” The long reed stung my scalp when he whipped it across my head. “Again!”

The days had proven warmer as the boat headed north, and Meryre’s spirit had weakened since he’d received a summons two days prior from the pharaoh’s daughter. He would say nothing more. He packed small bags for us and dragged me to the Nile’s shore at early dawn. The boatsmen were paid for silence, and he kept me working too hard to allow conversation.

I attempted forms half the morning while the boat swayed with the currents. Making brush strokes between the ebbs and flows took its toll on my patience, so I watched the reflections of daylight on the water. The river had begun to retreat from high ground, marking the season of peret with that pungent stench of silt and excrement. The floods had lasted longer than usual, giving good tidings from Isis—though it left us with less time to sow. Only the gods knew what that meant for next season and the season after.

It had been three floods since I began my apprenticeship with Meryre. I had been told he was an honored scribe from the north who came down our way to Thebes with a great thought school. His adept, a well-known and respected scribe, philosopher, and leader for our great pharaoh, Amenhotep III. I was not exceptional, but an exception. I had been but a street rat sheltered under an ass that brayed day into night until someone found me and took me to the priests. Aten shone down on me and gave me relief in the houses of the temple. In my eleventh year, I was put under the wing of this great fat man who snored like an ox. Why were we to this unheard-of city in the middle of nowhere between Thebes and Heliopolis?

“Ahem,” I uttered. Meryre didn’t budge. Louder, I said, “If it pleases you, master, I—”

“It would please me for you to leave me welcome the heat in peace.” He stayed as quiet as his constant grunting allowed before he pulled himself to a seated position at my face. “I am—” he stopped and fingered at the papyrus in his hand. “I am afforded a great honor with the royal wife of the two lands, in her house, may the goddesses bless me.”

His skin looked pallid against the sands as he spoke of blessed honors—as if he’d been asked to copulate with a sow. “Master, if it is a great privilege, why do you look burdened so?”

He refused an answer, so I returned to my writing, using both hands to steady the reed as I marked the curve of an owl’s wing. I could feel Meryre’s eyes drift from the waters to me and waited for another whack from behind with his reed, but he stayed quiet.

It relaxed me, the lapping of the waters, though the constant pitching of the boat made my work look like it was done by a crocodile rolling blood around on the page with a carcass. It was a pitiful sight, even I knew that, but he suffered my deficiency.

After a time, he pulled out a handful of clay shards from his sack and arranged them in a line at his feet. He then pulled a flint knife from his belt and began scratching, attempting care at first, making shallow scores, but after the first shard lost half of its identity, he became angry. I lifted my hand up, speechless, attempting in my own way to stop him. I was of no position to intervene in a master’s work.

By the time he reached the third shard he was aggressively slicing at images of the gods—Amun, Maat, and others lost their eyes, adornments, and flails. He chipped the stories of their interactions with the people of the two valleys until they were unrecognizable. Slivers of flint glittered in the sun and fell at Meryre’s feet.

“Master!” I eyed the boatsmen, who refused to look our way. They stayed their posts—it was no use to them seeing anything they must return home as secrets on their tongue. “Master, what are you doing?” I lunged and grabbed at the shards. I managed to pull the fourth away, but his knife caught and dragged across my forearm, leaving a spotted trail of blood.

Silence fell between us.

The sun left for its slumber, and Nuit’s starry blue dress appeared, sheltering us from the evil that crept at night. Smoke from small fires danced above the silt-covered furrows; the fields were squishy with abating flood waters and quick-drying mud. My arm pounded in unison with the drums that played in the village we passed, and Khonsu rose as a full disc, raining its white light on the Nile. The moon illuminated red the eyes of the crocodiles that waited for movement on the waters. I kept my hand over the trickling blood on my arm, refusing to weep. A boatsman quietly mended my wound with a bit of honey and mud, wrapping it with a small dressing.

“I’m sorry,” Meryre said once the moon rose well above the reeds.

“Master, I don’t understand—” He had never been cruel, but because he was not himself, I feared to continue pressing. “I’ll ready our beds.”

“No,” Meryre said. He pulled at my belt and pressed me to sit across from him, pouring beer into a cup from the decanter at his side. “Young apprentice, no words of honey will be leaving my lips, and for that reason, I command you hold your tongue once we set to shore.”

“Of course.”

“There is to be a new capital, between our home and the low lands. You will be given stay and well-kept for your affairs.”

“Why would Pharaoh move from Thebes?” It was not what I had wanted to say, and holding my tongue in my mouth made my face hot.

“The Pharaoh Akhenaten is to construct a new temple to Aten, where he is to lay utter worship to him and only him.”

“But, master, Thebes has many adequate temples, why—” What I wanted to say billowed as dry reeds on a campfire until it burst. “Had you told me we were not to return, I would have bid our home a proper parting, master. I very much wish—”

“No, Hap-mu, you fail to hear me. Thebes is no longer for us. The gods are no longer there. Only one god exists now—Akhenaten’s deity, Aten. As soon as we touch the river’s lips with our feet, we will no longer be allowed to utter a name that is not His. You will never return to Thebes, and you—” Words caught in his throat. “You will not be at my side. His royal wife Nefertiti will have me creating their new world under Aten. A temple not hidden in the dark like those before but in the open where we can worship him in the daylight. I know I can find a place for you, Hap-mu, but it will take time. Until then, I have arranged a job at the docks for you with a scribe there. You will never have to work in the fields—you will never have to go without, but you will not be with me.”

He grabbed my injured arm and held me in place. I felt snakes that wriggled hatred in my eyes. I wanted to jump off the boat and swim back to Thebes—or be eaten by the river. I wanted no more words from his mouth—each one uttered a profanity, and those words united became heresy; my master spoke falsehoods with every breath.

“You cannot,” I stuttered. “The very mention of it should strike down our boat. Akhenaten dishonors every god that sows his seeds and births his kin!” I picked up the defiled shards and threw them at his feet. “This is but practice for the entire city of Thebes? We are to erase the very gods that give us this river and the ink by which we make our living? You told me our way was of consequence, that our work was to live on until the last of us entered the Field of Reeds!”

“It is this or refuse and have us both struck down. It is a call that cannot be ignored.”

“You told me that you cannot change what is written, that a scribe writes to fill the page so that no falsehoods could fit between truths—a man can turn his head, but our truths are written on all sides—that an obelisk will light the path of truth to the four corners of our kingdom.”

“Apprentice, one day you will understand that the word of God is only heard by our great pharaoh. If the gods have told him this, then this will be written. The four corners of truth will know it whether we scrape at its face or not.”

Meryre

“Master Meryre, I found this in the commons.” A boy holds a small stone. On it, a prayer to Neper scrawled with ash, asking for bountiful crops without rot. “They hid it in a bread mold. Shall I hand it over to Iabi?”

“No. I’ll take it.”

“If it pleases you. Senebty.”

The boy scutters off with the other young apprentices now in my care. They are talkative, hard-skulled, and uninterested in learning. All of them wish only to work by the boats to mark supply and inventory; none desire knowledge, and only one is grown enough to remember old gods. Five floods had passed since my move to Akhetaton, and nothing about this place feels like home to anyone except possibly Aten himself.

I sit under the heel of Queen Nefertiti and her soldiers as they scour common housing for idols of taboo deities. My duty is to her and Him, Akhenaten—commanded to hunt those I once worshiped and gave offerings. For this, I am owed, and I am given. They keep me in well esteem. They decorate my home on the palace grounds with fine linens and a bed made of wood. My neck reflects boldly the rays of Aten from pendants adorned with lapis and topaz, and my belly rides full of fruits and beer. I stand at the head of esteemed academics and royal guards, talking the philosophy of self with priests, and attend temple festivals.

But the city of Akhetaton stands as a disfigurement against Egypt. I walk it this day, through the narrow streets, holding a mirror that reflects an ugliness that scars the kingdom. Shabby homes leave barely room for stove or pantry and fold into each other with no space for two to pass. The silos for grain and corn are built poorly and nag attention from pests. The pharaoh had built this city for himself. He wished to look down upon his people, but he looks down upon the most hideous city yet seen by man.

It is I who is charged with polishing scarab dung until it turns to gold. I love for Aten but I see cracks from ill-weathered plaster on the palace of the king. His wife Nefertiti sits on the throne next to him and whispers what words come on the breeze. Akhenaten knows of hidden worship to the old gods and he does not arrest those that do, but he keeps the idols in a room that gather more treasure than his own court. The gifts of my office delay the anger that builds inside me, and I do not know how long I can mark true the longevity of Aten alone. Destroying the names of the gods and goddesses etched in Thebes storms a darkness across the lands that keeps its hold on me. I fear all the linens and jewels in the valley will not make comfort of my time after life.

Should I have chosen death for my young pupil Hap-mu and me when the scroll came? Hap-mu’s life now I do not know, and am too afraid to glimpse, though I learned only that he worked among the priests’ quarters. Would death have been the cost of refusal, or could Hap-mu and I have continued quietly to live in Thebes—turning from scraping our souls away with each disfigurement and choosing to live simpler lives on the shore? What life I have carved for us from stone that expels shards into our eyes with every blow of the hammer!

“Master Meryre!”

The children find something—they are proud of themselves. My belly shoots pain to my heart. Oh! How I wish Nefertiti allowed us to stay inside and work on lessons instead of recruiting my young students to find people’s hidden hopes and watch them delight in wresting them from their fists.

They stand at the entry to a grain silo. The family’s eyes look past me, cold, and watch the boys dance, joyous, as if they had found barrels full of honey.

“Away,” I said. “Make way to the temple walls. We will finish with a lesson scribing a hymn to Aten.”

Entering the silo alone, I make out a small area covered with dried reeds. I lift the false floor, and there sits an icon of my great master Thoth, scribe of Maat in the company of the gods. Under him lay a tattered papyrus, barely legible, with a prayer to the old god Amun from the late Huy—my adept long ago.

I sit and pray hymns to Thoth, silently weeping in the dark of the grain silo at dusk, wishing for all the gods to hear my pleas.

Huy

A young man watches me from the corridors. Every day he sits in the dark and scrawls on pots, hiding them among the discarded oddments of the past. I do not know what he scribbles, but he thinks well to conceal his thoughts among the rubbish that no man wants to see—what was once confined to a single room now spills into every hall and chamber of the palace. Idols of deities decorate every crevice with insults to both the king and the god that houses them. The gaunt pharaoh Akhenaten tore everything away from the people that came to his city. Their words now spit in the eye of every priest and royal that hid behind these walls. I’ve been in this temple from the first mud shaped to home. I am the reason for the first room in this valley—a prison to hide away what came before.

I urge to know what truths the young man writes for himself, hiding away from the blinding light of Aten.

He considered me but once during his time away from the sun, a day when I scrawled on the walls with rust from the bowl I am given water. Even now, I am forbidden from writing, though the city slowly grows over itself, and the sounds of the people busying in the streets have quieted. Only mutterings from abandoned animals and shouts from the few guards left to protect Akhenaten and his reviled queen remain. I find stolen moments to practice my forms—to write memories to project the truth to the gods above. I clang my cup against the small window of my room so that I might catch his attention.

“Boy.” My voice is out of practice, more than my writings. It’s barely a rattling whisper against the winds. He looks, making quick glances before sneaking his way to me. He is silent, and his eyes stay on the ground. “Your name, boy.”

“I am no boy. I am Hap-mu.”

His voice cracks like mine, dusty as empty uncorked jars that hold nothing but time.

“To me, you are barely out of childhood. Your bones are strong, and your skin reflects the light. You walk with a strong name. What profanities do you write on pots that they must be concealed?”

“Not profanities,” he snaps. “Only practice. Or—well, truths, as I remember them. Profanity is what I have done in my years here since. I—”

He looks into my small quarters. I am embarrassed at my crude work. Crooked forms of vultures point to jagged cartouches, cradling names of pharaohs of a time long since passed. Descriptions of grand Sed festivals speak of wealth and peace. The rusty ink bleeds down the wall, each symbol made with a pen crafted with hairs from my head.

“What old prisoner knows of such great histories?” Hap-mu says. “Surely, these are only the musings of dreaming while awake—madness from the dark.”

“No, young Hap-mu, they are truths hidden by our pharaoh and his court from time before his reign.”

I tell him my story, guiding him with the memories scribbled on the walls. I am Huy, scribe and trusted official amongst our last great pharaoh, Akhenaten’s revered father, Amenhotep III. I speak of a young Akhenaten, who cared nothing of the kingdom or of governance, who hated his father and everything he stood for, who at a young age decided to cut down all that he found beneath him as a ruler. I, who stood against him when he was only a boy, was taken under the dead of night by guards allegiant with the soon-to-be boy king and thrown into a cave outside Thebes’ borders. My great ruler thought me dead long before the boy took the throne, and as Amenhotep III was sent to the Field of Reeds, his son already had begun his plan. Obsession took him early, and the cult of Aten grew in the shadows until he chose the spot to hide me away at the center of his new domain. I tell him of watching through my small window as they erected obelisks that only shout to the sun god, and all mention of the past I wrote as hymns were scraped from the eyes of the people—scroll, pot, and temple alike.

He weeps as I tell my story, clutching the knife he used to carve his truths into clay.

“The profanities I speak of,” he says, “are those you condemn. I was brought here with my adept Meryre under command from the queen to oversee the removal of all things old gods. I spent my first six floods with the priests, rewriting lies over truth, filling in spaces to tell tales. I was made to spread the pulp of acidic fruits to ink and watch our history be eaten away. I could not bear it, though I watched Meryre rise to the occasions of inaccuracy. I ran to the dark of the priests’ homes instead of living in the temple of false light.”

My heart sinks deep.

“Wait.” Hap-mu’s confession rings deaf in my ears as soon as he speaks the name of his adept. I do not know what could make lightness of my soul evermore. “Meryre, my young student from the lower valley, is the one that rips beliefs from the people?”

“Yes,” Hap-mu says. “He lives now, wearing a fatter belly than he came with more than twenty floods ago, catering to Nefertiti’s harem and seeing to the treasures that we hold inside. He left truth to live in the lying light.”

“The gods will know of his deceit, young Hap-mu, and they will know the truth in your heart. Your weight will ring as a feather against the evil done to you.”

“I will be forced to be scribe only to what the heretic queen desires. How will they know my wishes from my actions, master Huy?”

“Be steady in your desire, young student. Amun, the great creator behind the clouds, calls for storm. His high priest travels from Thebes and visits me in the corridors, behind the watchful eyes shining down from Aten. He tells me tales of the people at our rightful capital readying themselves for the return to what should be.”

“When?” he asks. “I can open your prison and leave with you now, were it your desire. I want to find peace in truth.”

“I am old and too tired for the journey, but take with you what you learn. The gods will again guide you should you find yourself back under the blanket of Maat.”

Hap-mu

Akhenaten was dead. The people abandoned his beautiful queen Nefertiti, the temple, and their god. An army of priests and guards rushed through the city a mere week after the reviled king’s passing. They entered his tomb, carving out his and his family’s faces. His supposed followers chanted hymns to the old capital’s deity Amun, trampling and disfiguring Aten’s outdoor Sun Temple north of the city center.

Huy, my master through prison walls, died a few years after we first met. When the priests came to throw his body into a mass grave with temple builders, I stood at the gate and refused them passage. I bade them leave his body and prison walls alone and waited for the high priest that visited him from Thebes. The priest snuck his body out to be properly interred back in the capital proper.

The years pressed on, and I spent my time in his prison. I ripped the hinges from the door that never opened for him and used it as my chambers. I continued his work, using rust and ash to practice form, write truths, and pray to the gods forbidden from the city borders. When the army came to tear down what the heretic built, they found me in the dark, hiding from Aten’s light, writing to the gods they sought to bring back to the people. They read the inscriptions that lined every space, filled with histories told and those almost lost to memory. Thebes’ priests left and returned to help me preserve carved slabs from the mud brick—Huy’s writings were to live on, away from the stains this place laid upon the two lands.

On a royal boat I sat between two caskets, in the company of the new boy-king, Tutankhaten. To my left, a simple clay one with the life written of Meryre, the queen’s royal scribe, overseer, and my old master. The inscriptions showed a remarkable rise to power and his loyalty to the crown. To my right was an ornately carved stone sarcophagus of the heretic king himself.

Tutankhaten approached and sat next to me with a golden knife in his hand. His white linens were pristine around his waist, and a carved lapis image of Amun glittered at his chest. He pressed the knife’s handle into my hands and motioned at the sarcophagi.

“I cannot,” I said. “It is my purpose to press pen and ink to stone to tell your story.”

“Your purpose,” he said, “is to tell truths. Leave the stories, if you wish, but those names will not live on in the memories of those in Thebes.”

“Who am I to speak against the very offenses I commit?”

The boy-king smiled at me and pat me on the shoulder. “The gods welcome us with open arms back in Thebes. Their pillars and obelisks cry faceless into the starry night. They want their names returned to them in the mouths of the people. We will bring it. You, Hap-mu, will bring that. The gods know of your loyalty to them and to the throne. The age of the enemies is over. Now, while I reign, peace will fall as a warmth over the lands of Egypt once again.”

“The tablets I insisted come on the boat here with us; those are truths from your grandfather and my honorable master, Huy. He is a man of great reverence.”

“Then he shall be revered just as you, royal scribe.”

***